DIAMOND CUTS

Share

| A diamond cut is a style or design guide used when shaping a diamond for polishing such as the brilliant cut. Cut refers to shape (pear, oval), and also the symmetry, proportioning and polish of a diamond. The cut of a diamond greatly affects a diamond's brilliance—a poorly-cut diamond is less luminous. |

In order to best use a diamond gemstone's material properties, a number of different diamond cuts have been developed. A diamond cut constitutes a more or less symmetrical arrangement of facets, which together modify the shape and appearance of a diamond crystal. Diamond cutters must consider several factors, such as the shape and size of the crystal, when choosing a cut. The practical history of diamond cuts can be traced back to the Middle Ages, while their theoretical basis was not developed until the turn of the 20th century. Design, creation and innovation continue to the present day: new technology—notably laser cutting and computer-aided design—has enabled the development of cuts whose complexity, optical performance, and waste reduction were hitherto unthinkable.

The most popular of diamond cuts is the modern round brilliant, whose facet arrangements and proportions have been perfected by both mathematical and empirical analysis. Also popular are the fancy cuts, which come in a variety of shapes, many of which were derived from the round brilliant. A diamond's cut is evaluated by trained graders, with higher grades given to stones whose symmetry and proportions most closely match the particular "ideal" used as a benchmark. The strictest standards are applied to the round brilliant; although its facet count is invariable, its proportions are not. Different countries base their cut grading on different ideals: one may speak of the American Standard or the Scandinavian Standard (Scan. D.N.), to give but two examples.

History

Ancient India

The process of diamond cutting has been known in the Indian subcontinent as early as the sixth century AD. A sixth-century treatise Ratnapariksa, or "Appreciation of Gems", states that the best form in which to have the diamond is in its perfect natural octahedral crystal form, and not as a cut stone, indicating that diamond cutting was widespread practice.[1] Al Beruni also describes the process of diamond grinding using lead plate in the 11th century AD.[2] Agastimata, written before 10th century AD, states:[3]

The diamond cannot be cut by means of metals and gems of other species; but it also resists polishing, the diamond can only be polished by means of other diamonds

— Agastimata

A 12th- or early 13th-century diamond ring attributed to Muhammad Ghauri contains two diamonds whose crude octahedral natural states are maintained, but they are in limpid condition, exhibiting diamond polishing and shaping predating Europe, where the first diamond processing dates back to the mid-14th century AD.[4] As of today, few diamonds with ancient Mughal style faceting are known.[5]

Europe

The history of diamond cuts in Europe can be traced to the late Middle Ages, before which time diamonds were employed in their natural octahedral state—anhedral (poorly formed) diamonds simply were not used in jewelry. The first "improvements" on nature's design involved a simple polishing of the octahedral crystal faces to create even and unblemished facets, or to fashion the desired octahedral shape out of an otherwise unappealing piece of rough. This was called the point cut and dates from the mid 14th century; by 1375 there was a guild of diamond polishers at Nürnberg. By the mid 15th century, the point cut began to be improved upon: the top of the octahedron would be polished or ground off, creating the table cut. The importance of a culet was also realised, and some table-cut stones may possess one. The addition of four corner facets created the old single cut (or old eight cut). Neither of these early cuts would reveal what diamond is prized for today; its strong dispersion or fire. At the time, diamond was valued chiefly for its adamantine lustre and superlative hardness; a table-cut diamond would appear black to the eye, as they do in paintings of the era. For this reason, colored gemstones such as ruby and sapphire were far more popular in jewelry of the era.

In or around 1476, Lodewyk (Louis) van Berquem, a Flemish polisher of Bruges, introduced the technique of absolute symmetry in the disposition of facets using a device of his own invention, the scaif. He cut stones in the shape known as pendeloque or briolette; these were pear-shaped with triangular facets on both sides. About the middle of the 16th century, the rose or rosette was introduced in Antwerp: it also consisted of triangular facets arranged in a symmetrical radiating pattern, but with the bottom of the stone left flat—essentially a crown without a pavilion. Many large, famous Indian diamonds of old (such as the Orloff and Sancy) also feature a rose-like cut; there is some suggestion that Western cutters were influenced by Indian stones, because some of these diamonds may predate the Western adoption of the rose cut. However, Indian "rose cuts" were far less symmetrical as their cutters had the primary interest of conserving carat weight, due to the divine status of diamond in India. In either event, the rose cut continued to evolve, with its depth, number and arrangements of facets being tweaked.

The first brilliant cuts were introduced in the middle of the 17th century. Known as Mazarins, they had 17 facets on the crown (upper half). They are also called double-cut brilliants as they are seen as a step up from old single cuts. Vincent Peruzzi, a Venetian polisher, later increased the number of crown facets from 17 to 33 (triple-cut or Peruzzi brilliants), thereby significantly increasing the fire and brilliance of the cut gem, properties that in the Mazarin were already incomparably better than in the rose. Yet Peruzzi-cut diamonds, when seen nowadays, seem exceedingly dull compared to modern-cut brilliants. Because the practice of bruting had not yet been developed, these early brilliants were all rounded squares or rectangles in cross-section (rather than circular). Given the general name of cushion—what are known today as old mine cuts—these were common by the early 18th century.

Around 1860, American jeweler Henry Dutton Morse opened the first American diamond cutting factory in Boston. Assuming that smaller but more beautiful gems will sell better, he went against the dogma of conserving diamond weight at all costs and scientifically studied refraction in diamonds, by around 1870 developing what was called the old European cut much later.[6] This cut had a shallower pavilion, more rounded shape thanks to Morse's foreman Charles M. Field who developed mechanical diamond bruting machine to replace manual rounding (the two also introduced dimensional gauges to the industry), and different arrangement of facets. The old European cut was the forerunner of modern brilliants and was the most advanced in use during the 19th century and first two decades of the 20th century, prevailing on the market from about 1890 until about 1930.[7] As compared with the modern round brilliant cut, it is inferior in brilliance but superior in fire.[8]

Around the turn of the century, the development of motorized rotary saws for cutting diamonds, patented in 1901 by John H. G. Stuurman[9] and in 1902 by Ernest G. H. Schenck,[10] gave cutters creative freedom to separate small stones not detachable by cleaving as they wish and allowed them to waste less. These diamond saws and good jewelry lathes enabled the development of modern diamond cutting and diamond cuts, chief among them the round brilliant cut. In 1919, Marcel Tolkowsky analyzed this cut: his calculations took both brilliance (the amount of white light reflected) and fire into consideration, creating a delicate balance between the two.[11] Tolkowsky's calculations would serve as the basis for all future brilliant cut modifications and standards.

Tolkowsky's model of the "ideal" cut is not perfect. The original model served as a general guideline, and did not explore or account for several aspects of diamond cut:[12]

Because every facet has the potential to change a light ray's plane of travel, every facet must be considered in any complete calculation of light paths. Just as a two-dimensional slice of a diamond provides incomplete information about the three-dimensional nature of light behavior inside a diamond, this two-dimensional slice also provides incomplete information about light behavior outside the diamond. A diamond's panorama is three-dimensional. Although diamonds are highly symmetrical, light can enter a diamond from many directions and many angles. This factor further highlights the need to reevaluate Tolkowsky's results, and to recalculate the effects of a diamond's proportions on its appearance aspects. ...

Another important point to consider is that Tolkowsky did not follow the path of a ray that was reflected more than twice in the diamond. However, we now know that a diamond's appearance is composed of many light paths that reflect considerably more than two times within that diamond. Once again, we can see that Tolkowsky's predictions are helpful in explaining optimal diamond performance, but they are incomplete by today's technological standards.

Tolkowsky's guidelines, while revolutionary in their day, are not a definitive solution to the problem of finding the optimum proportions of a round brilliant cut diamond.

In the 1970s, Bruce Harding developed another mathematical model for gem design. Since then, several groups have used computer models[11][13] and specialized scopes to design diamond cuts.

The world's top diamond cutting and polishing center is India. It processes 11 out of 12 diamonds in jewelry worldwide. The sector employs 1.3 million people and accounts for 14% of India's $80 billion of annual exports. Its share in the world polished diamond market is 92% by pieces and 55% by value.

Theory

In its rough state, a diamond is fairly unremarkable in appearance. Most gem diamonds are recovered from secondary or alluvial deposits, and such diamonds have dull, battered external surfaces often covered by a gummy, opaque skin—a comparison to "lumps of washing soda" is apt. The act of polishing a diamond and creating flat facets in symmetrical arrangement brings out the diamond's hidden beauty in dramatic fashion.

When designing a diamond cut, two primary factors are considered. Foremost is the refractive index (RI) of a diamond, which, at 2.417 (as measured by sodium light, 589.3 nm), is fairly high compared with that of most other gems. Diamond's RI is responsible for its brilliance—the amount of incident light reflected back to the viewer. Also important is a diamond's dispersive power—the ability of the material to split white light into its component spectral colors—which is also relatively high, at 0.044 (as measured from the B-G interval). The flashes of spectral colors—known as fire—are a function of this dispersion, but are, like brilliance, only apparent after cutting.

Brilliance can be divided into the definitions external brilliance and internal brilliance. The former is the light reflected from the surface of the stone—its luster. Diamond's adamantine ("diamond-like") luster is second only to metallic (i.e., that of metals); while it is directly related to RI, the quality of a finished gem's polish determines how well a diamond's luster is borne out.

Internal brilliance—the percentage of incident light reflected back to the viewer from the rear (pavilion) facets—relies on careful consideration of a cut's interfacial angles as they relate to diamond's RI. The goal is to attain total internal reflection (TIR) by choosing the crown angle and pavilion angle (the angle formed by the pavilion facets and girdle plane) such that the reflected light's angle of incidence (when reaching the pavilion facets) falls outside diamond's critical angle, or minimum angle for TIR, of 24.4°. Two observations can be made: if the pavilion is too shallow, light meets the pavilion facets within the critical angle, and is refracted (i.e., lost) through the pavilion bottom into the air. If the pavilion is too deep, light is initially reflected outside the critical angle on one side of the pavilion, but meets the opposite side within the critical angle and is then refracted out the side of the stone.[14]

The term scintillation brilliance is applied to the number and arrangement of light reflections from the internal facets; that is, the degree of "sparkle" seen when the stone or observer moves. Scintillation is dependent on the size, number, and symmetry of facets, as well as on quality of polish. Tiny stones appear milky if their scintillation is too great (due to the limitations of the human eye), whereas larger stones appear lifeless if their facets are too large or too few.

A diamond's fire is determined by the cut's crown height and crown angle (the crown being the top half of the stone, above the girdle), and the size and number of facets that compose it. The crown acts as a prism: light exiting the stone (after reflection from the pavilion facets) should meet the crown facets at as great an angle of incidence from the normal as possible (without exceeding the critical angle) in order to achieve the greatest fanning out or spread of spectral colors. The crown height is related to the crown angle, the crown facet size, and the table size (the largest central facet of the crown): a happy medium is sought in a table that is not too small (resulting in larger crown facets and greater fire at the expense of brilliance) or too large (resulting in smaller crown facets and little to no fire).

Polish and symmetry

Polish and symmetry are two important aspects of the cut. The polish describes the smoothness of the diamond's facets, and the symmetry refers to alignment of the facets. With poor polish, the surface of a facet may be scratched or dulled, and may cause a blurred or dulled sparkle. While most polish defects are a result of the cutting process, some surface flaws are a result of defects in the natural stone. One example is grain lines (produced when irregular crystallization occurs as a diamond is formed) running across the facet. Severe polish defects may cause the diamond to constantly look like it needs to be cleaned. With poor symmetry, light can be misdirected as it enters and exits the diamond.

Choice of cut

The choice of diamond cut is often decided by the original shape of the rough stone, location of internal flaws or inclusions, the preservation of carat weight, and popularity of certain shapes among consumers. The cutter must consider each of these variables before proceeding.

Most gem-quality diamond crystals are octahedra in their rough state (see material properties of diamond). These crystals are usually cut into round brilliants because it is possible to cut two such stones out of one octahedron with minimal loss of weight. If the crystal is malformed or twinned, or if inclusions are present at inopportune locations, the diamond is more likely to receive a fancy cut (a cut other than a round brilliant). This is especially true in the case of macle, which are flattened twin octahedron crystals. Round brilliants have certain requisite proportions that would result in high weight loss, whereas fancy cuts are typically much more flexible in this regard. Sometimes the cutters compromise and accept lesser proportions and symmetry in order to avoid inclusions or to preserve carat weight, since the per-carat price of diamond is much higher when the stone is over one carat (200 mg).

While the round brilliant cut is considered standard for diamond, with its shape and proportions nearly constant, the choice of fancy cut is influenced heavily by fashion. For example, the step cut baguette—which accentuates a diamond's luster, whiteness, and clarity but downplays its fire—was all the rage during the Art Deco period, whereas the mixed Princess cut—which accentuates a diamond's fire and brilliance rather than its luster—is currently[when?] gaining popularity. The princess cut is also popular among diamond cutters because, of all the cuts, it wastes the least of the original crystal. Older diamonds cut before ca. 1900 were cut in "primitive" versions of the modern round brilliant, such as the rose cut and old mine cut (see History section). Although there is a market for antique stones, many are recut into modern brilliants to increase their marketability. There is also increasing demand for diamonds to be cut in older styles for the purpose of repairing or reproducing antique jewelry.

The size of a diamond may also be a factor. Tiny (< 0.02 carats [4 mg]) diamonds—known as melée—are usually given simplified cuts (i.e., with fewer facets). This is because a full-cut brilliant of such small size would appear milky to the human eye, owing to its inability to resolve the stone's dispersive fire. Conversely, large diamonds are usually given fancy cuts with many extra facets. Conventional round brilliant or fancy cuts do not scale up satisfactorily, so the extra facets are needed to ensure there are no "dead spots". Because large diamonds are less likely to be set in jewelry, their cuts are considered for how well they display the diamonds' properties from a wide range of viewing directions; in the case of more moderate-sized diamonds, the cuts are considered primarily for their face-up appeal.

The dominating round brilliant diamonds are not as trendy as they used to be since the market was overcrowded in the last decades of the century.[15] Simultaneously, giving a fancy diamond cut as a precious jewel on specific celebrations became a part of tradition. A Heart cut diamond has romantic symbolism so it is a common gift for Valentine's Day or wedding anniversary. The pear-shaped diamonds look like a drop of water and the shape is suitable for diamond earrings. The most famous shapes are: Princess, Cushion, Heart, Pear, Marquise, Radiant, Asscher cut, Emerald, Oval.[16]

Round brilliant

Developed c. 1900, the round brilliant is the most popular cut given to diamond. It is usually the best choice in terms of saleability, insurability (due to its relatively "safe" shape), and desired optics.

Facet count and names[edit]

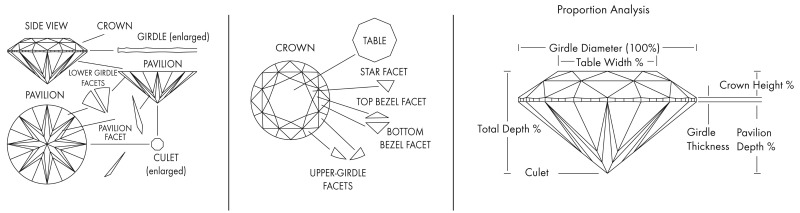

The modern round brilliant (Figure 1 and 2) consists of 58 facets (or 57 if the culet is excluded); 33 on the crown (the top half above the middle or girdle of the stone) and 25 on the pavilion (the lower half below the girdle). The girdle may be frosted, polished smooth, or faceted. In recent decades, most girdles are faceted; many have 32, 64, 80, or 96 facets; these facets are excluded from the total facet count. Likewise, some diamonds may have small extra facets on the crown or pavilion that were created to remove surface imperfections during the diamond cutting process. Depending on their size and location, they may hurt the symmetry of the cut and are therefore considered during cut grading.

Figure 1 assumes that the "thick part of the girdle" is the same thickness at all 16 "thick parts". It does not consider the effects of indexed upper girdle facets.[17] Figure 2 is adapted from the Tolkowsky book,[18] originally published in 1919. Since 1919, the lower girdle facets have become longer. As a result, the pavilion main facets have become narrower.

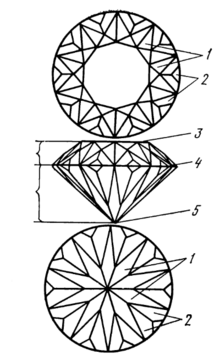

Proportions

While the facet count is standard, the actual proportions—crown height and crown angle, pavilion depth and pavilion angle, and table size—are not universally agreed upon. There are at least six "ideal cuts" that have been devised over the years, but only three are in common use as a means of benchmarking. Developed by Marcel Tolkowsky in 1919, the American Standard (also known as the American Ideal and Tolkowsky Brilliant) is the benchmark in North America. It was derived from mathematical calculations that considered both brilliance and fire. The benchmark in Germany and other European countries is the Practical Fine Cut (German: Feinschliff der Praxis, also known as the Eppler Cut), introduced in 1939. It was developed in Germany by empirical observations and differs only slightly from the American Standard. Introduced as part of the Scandinavian Diamond Nomenclature (Scan. D. N.) in 1969, the Scandinavian Standard also differs slightly.

Other benchmarks include: the Ideal Brilliant (developed in 1929 by Johnson and Roesch), the Parker Brilliant (1951), and the Eulitz Brilliant (1968)[19] The Ideal and Parker brilliants are disused because their proportions result in (by contemporary standards) an unacceptably low brilliance. The Eulitz cut is the only other mathematically derived benchmark; it is also historically the only benchmark to consider girdle thickness. A more modern benchmark is that set by Accredited Gem Appraisers (AGA). Although their standard generally makes a modern ideal cut it has been criticised for being overly strict. A summary of the different benchmarks is given below:

| Benchmark | Crown height |

Pavilion depth |

Table diameter |

Girdle thickness |

Crown angle |

Pavilion angle |

Brilliance grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGA | 14.0–16.3% | 42.8–43.2% | 53–59% | — | 34.0–34.7° | — | 100% |

| American Standard | 16.2% | 43.1% | 53.0% | — | 34.5° | 40.75° | 99.5% |

| Eulitz Brilliant | 14.45% | 43.15% | 56.5% | 1.5% | 33.6° | 40.8° | 100% |

| Ideal Brilliant | 19.2% | 40.0% | 56.1% | — | 41.1° | 38.7° | 98.4% |

| Parker Brilliant | 10.5% | 43.4% | 55.9% | — | 25.5° | 40.9° | Low |

| Practical Fine Cut | 14.4% | 43.2% | 56.0% | — | 33.2° | 40.8° | 99.95% |

| Scandinavian Standard | 14.6% | 43.1% | 57.5% | — | 34.5° | 40.75° | 99.5% |

Crown height, pavilion depth, and table diameter are percentages of the total girdle diameter. Because the pavilion angle (and consequently pavilion depth) is so closely tied to total internal reflection, it varies the least between the different standards.

Hearts and arrows phenomenon

The term "hearts and arrows" is used to describe the visual effect achieved in a round brilliant cut diamond with perfect symmetry and angles that exhibit a crisp and complete pattern of hearts and arrows. When viewed under a special magnifying viewer, a complete and precise visual pattern of 8 hearts is seen while looking down through the pavilion, and 8 arrows can be seen when viewing the stone in the table up position.

Passion cut

Another modification of the round ideal cut that maintains the basic proportions of its angles is the passion cut.[20] This cut's design can be considered the opposite of the hearts and arrows, as it eliminates the arrows in order to capture a different light return from the center of the diamond. The cut splits the eight pavilion mains and increases the specifically-placed total facets from 57 to 81. The cut was designed to enhance brilliance and mask inclusions.

Fancy cuts

Even with modern techniques, the cutting and polishing of a diamond crystal always results in a dramatic loss of weight; rarely is it less than 50%. The round brilliant cut is preferred when the crystal is an octahedron, as often two stones may be cut from one such crystal. Oddly-shaped crystals such as macles are more likely to be cut in a fancy cut (that is, a cut other than the round brilliant), which the particular crystal shape lends itself to. The prevalence and choice of a particular fancy cut is also influenced by fashion; generally speaking, these cuts are not held to the same strict standards as Tolkowsky-derived round brilliants. Most fancy cuts can be grouped into four categories: modified brilliants, step cuts, mixed cuts, and rose cuts.

Modified brilliants

This is the most populous category of fancy cut, because the standard round brilliant can be effectively modified into a wide range of shapes. Because their facet counts and facet arrangements are the same, modified brilliants also look (in terms of brilliance and fire interplay) the most like round brilliants.

Modified brilliants include the marquise (a prolate lemon-shape, also called navette, which is French for "little boat", because it resembles the hull of a sailboat), heart, triangular trillion (also trillian or trilliant), oval, and the pear or drop cuts. These are the most commonly encountered modified brilliants; Oval-shaped diamonds have been created and introduced by Lazare Kaplan way back in the 1960s. Usually noted to have 56 facets, the weight of such diamonds is estimated by measuring the length and width of the stone. A ratio of 1.33 to 1.66 provides a good traditional range of oval-shaped diamonds. Pear-shaped diamonds are also known as the teardrop shape owing to their resemblance and is considered as a hybrid between the marquise cut and the round brilliant diamond. The stone has one end rounded while the other end is pointed. Pear shape diamonds can opt between varying length and width ratios for the ideal looking pear-shaped diamond. Length to width ratios between 1.45 and 1.75 are most common.

Modern cutting technology has allowed the development of increasingly complex and hitherto unthinkable shapes, such as stars and butterflies. Their proportions are mostly a matter of personal preference; however, due to their sharp terminations and diamond's relative fragility, these cuts are more vulnerable to accidental breakage and may therefore be more difficult to insure.

There are several older modified brilliant cuts of uncertain age that, while no longer widely used, are notable for history's sake. They are all round in outline and modify the standard round brilliant by adding facets and changing symmetry, either by dividing the standard facets or by placing new ones in different arrangements. These cuts include: the King and Magna cuts, both developed by New York City firms, with the former possessing 86 facets and 12-fold symmetry and the latter with 102 facets and 10-fold symmetry; the High-Light cut, developed by Belgian cutter M. Westreich, with 16 additional facets divided equally between the crown and pavilion; and the Princess 144, introduced in the 1960s, with 144 facets and 8-fold symmetry. Not to be confused with the mixed Princess cut, the Princess 144 cut makes for a lively stone with good scintillation; the extra facets are cut under the girdle rather than subdivided. The extra care required for these sub-girdle facets benefits the finished stone by mitigating girdle irregularity and bearding (hairline fracturing). Today, with the increased understanding of light dynamics and diamond cutting, many companies have developed new, modified round brilliant cut diamonds. If designed correctly, these extra facets of the modified round brilliant could benefit the overall beauty of a diamond, such as in 91 facet diamonds.

Step cuts

Stones whose outlines are either square or rectangular and whose facets are rectilinear and arranged parallel to the girdle are known as step- or trap-cut stones. These stones often have their corners truncated, creating an emerald cut (after its most common application to emerald gemstones) with an octagonal outline. This is done because sharp corners are points of weakness where a diamond may cleave or fracture. Instead of a culet, step-cut stones have a keel running the length of the pavilion terminus. Like other fancy shaped diamonds, emerald cut diamonds can come in a variety of length to width ratios. The most popular and classic outline of emerald cut diamonds are close a value of 1.5.

The Asscher cut, a square modified emerald cut, is also popular.

Because both the pavilion and crown are comparatively shallow, step cut stones are generally not as bright and never as fiery as brilliant cut stones, but rather accentuate a diamond's clarity (as even the slightest flaw would be highly visible), whiteness, and lustre (and therefore good polish).

Due to the current[when?] vogue for brilliant and brilliant-like cuts, step cut diamonds may suffer somewhat in value; stones that are deep enough may be re-cut into more popular shapes. However, the step cut's rectilinear form was popular in the Art Deco period. Antique jewelry of the period features step-cut stones prominently, and there is a market in producing new step-cut stones to repair antique jewelry or to reproduce it. The slender, rectangular baguette (from the French, resembling a loaf of bread) was and is the most common form of the step cut: today, it is most often used as an accent stone to flank a ring's larger central (and usually brilliant-cut) stone.

Square step cuts whose corners are not truncated are known as carré; they are also characteristic of antique jewelry. They may resemble the square-shaped Princess cut in passing, but a carré's lack of fire and simpler facets are distinctive. They may or may not have a culet. In Western jewelry dating to before the advent of brilliant-type cuts, shallow step-cut stones were used as lustrous covers for miniature paintings: these are known in the antique trade as portrait stones. Characteristic of Indian jewelry are lasque diamonds, which may be the earliest form of step cut. They are flat stones with large tables and asymmetric outlines.

Other forms of the step cut include triangle (or Trilliant cut), kite, lozenge, trapeze (or trapezoid), and obus shapes.

Mixed cuts

Mixed cuts share aspects of both (modified) brilliant and step cuts: they are meant to combine the weight preservation and dimensions of step cuts with the optical effects of brilliants. Typically the crown is brilliant cut and the pavilion step-cut. Mixed cuts are all relatively new, with the oldest dating back to the 1960s. They have been extremely successful commercially and continue to gain popularity, loosening the foothold of the de facto standard round brilliant.

Among the first mixed cuts was the Barion cut, introduced in 1971. Invented by South African diamond cutter Basil Watermeyer and named after himself and his wife Marion, the basic Barion cut is an octagonal square or rectangle, with a polished and faceted girdle. The total facet count is 62 (excluding the culet): 25 on the crown; 29 on the pavilion; and 8 on the girdle. This cut can be easily identified by the characteristic central cross pattern (as seen through the table) created by the pavilion facets, as well as by the crescent-shaped facets on the pavilion. A similar cut is the Radiant cut: It differs in having a total of 70 facets. Both it and the Barion cut exist in a large number of modified forms, with slightly different facet arrangements and combinations.

The most successful mixed cut is the Princess cut, first introduced in 1960 by A. Nagy of London. It was originally intended for flat rough (macles), but has since become popular enough that some gemological labs, such as that of the American Gem Society (AGS), have developed Princess cut grading standards with stringency akin to standards applied to round brilliants. Its higher fire and brilliance compared to other mixed cuts is one reason for the Princess cut's popularity, but more importantly is the fact that, of all the diamond cuts, it wastes the least of the original crystal. Another beautiful cut is the Flanders cut, a modified square with cut corners, brilliant facets and is currently being cut by cutters at Russian Star.

Rose and mogul cuts

- Round brilliant, top view

- Oval brilliant, top view

- Rose cut, top view

- Round brilliant, side view

- Cushion brilliant, top view

- Rose cut, side view

- Step cut, octagon

- Pear brilliant, top view

- Step cut, oblong

- High cabochon, side view

- Lentil-shaped, side view

- Cabochon, side view

Various forms of the rose cut have been in use since the mid-16th century. Like the step cuts, they were derived from older types of cuts. The basic rose cut has a flat base—that is, it lacks a pavilion—and has a crown composed of triangular facets (usually 12 or 24) rising to form a point (there is no table facet) in an arrangement with sixfold rotational symmetry. The so-called double rose cut is a variation that adds six kite facets at the margin of the base. The classic rose cut is circular in outline; non-circular variations on the rose cut include the briolette (oval), Antwerp rose (hexagonal), and double Dutch rose (resembling two rose cuts united back-to-back). Rose-cut diamonds are seldom seen nowadays, except in antique jewelry. Like the older style brilliants and step cuts, there is a growing demand for the purpose of repairing or reproducing antique pieces.

Related to the rose cut, and of similar antiquity, is the mogul cut, named after the Great Mogul diamond that was the most famous example of its type. Like the classic rose cut, the mogul cut also lacks a pavilion and a table facet, and its crown is also composed of triangular facets rising to form a point. But in mogul-cut diamonds the rotational symmetry is normally fourfold or eightfold, and the eight apical facets are girded by two or more additional rings of facets. The modern mogul cut evolved from earlier faceting techniques originally used to disguise internal flaws in large stones;[11] in the modern day this cut has also become rare, but still finds occasional use where it is less important to showcase a stone's internal clarity, as with the black and internally opaque Spirit of de Grisogono Diamond.

Cut grading

The "Cut" of the "4 Cs" is the most difficult part for a consumer to judge when selecting a good diamond. This is because some certificates do not show the important measurements influencing cut (such as the pavilion angle and crown angle) and do not provide a subjective ranking of how good the cut was. The other three Cs can be ranked simply by the rating in each category. It requires a trained eye to judge the quality of a diamond cut, and the task is complicated by the fact that different standards are used in different countries (see proportions of the round brilliant).

The relationship between the crown angle and the pavilion angle has the greatest effect on the look of the diamond. A slightly steep pavilion angle can be complemented by a shallower crown angle, and vice versa. This trade-off has been quantified by independent authors, using various approaches.[21][22]

Other proportions also affect the look of the diamond:

- The table ratio is significant.

- The length of the lower girdle facets affects whether Hearts and arrows can be seen in the stone, under certain viewers.

- Most round brilliant diamonds have roughly the same girdle thickness at all 16 "thick parts".

- So-called "cheated" girdles have thicker girdles where the main facets touch the girdle than where adjacent upper girdle facets touch the girdle. These stones weigh more (for a given diameter, average girdle thickness, crown angle, pavilion angle, and table ratio), and have worse optical performance (their upper girdle facets appear dark in some lighting conditions).

- So-called "painted" girdles have thinner girdles where the main facets touch the girdle than where adjacent upper girdle facets touch the girdle. These stones have less light leakage at the edge of the stone (for a given crown angle, pavilion angle, and table ratio).[23]

Several groups have developed diamond cut grading standards. They all disagree somewhat on which proportions make the best cut. There are certain proportions that are considered best by two or more groups however.

- The AGA standards may be the strictest at the upper range of quality. David Atlas developed the AGA standards in the 1990s for all standard diamond shapes.[24]

- The HCA changed several times between 2001 and 2004. As of 2004, an HCA score below two represented an excellent cut. The HCA distinguishes between brilliant, Tolkowsky, and fiery cuts.

- The AGS standards changed in 2005 to better match Tolkowsky's model and Octonus' ray tracing results. The 2005 AGS standards penalize stones with "cheated" girdles. They grade from 0 to 10, with ranges corresponding to single descriptive words: Ideal (0), Excellent (1), Very Good (2), Good (3-4), Fair (5-7), Poor (8-10).[25]

- The GIA began grading cut on every grading report for round brilliant beginning in 2006[26] based on their comprehensive study of 20,000 proportions with 70,000 observations of 2,000 diamonds.[citation needed] The single descriptive words are as follows: Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, and Poor.[25]

The distance from the viewer's eye to the diamond is important. The 2005 AGS cut standards are based on a distance of 25 centimeters (about 10 inches). The 2004 HCA cut standards are based on a distance of 40 centimeters (16 in).

- Various labs around the world are using ImaGem's VeriGem device to measure light behavior. DGLA in the US and Mumbai, India, PGGL in the US and EGL-USA are both offering versions of this grading in 2008. DGLA has graded thousands of diamonds with this promising direct assessment technology.

- "Brilliancescope" by Gemex is another assessment light behavior technology in use by many US and now foreign retailers and diamond cutters.

Effect of cut on other diamond characteristics

During the diamond cutting process, the diamond cutter wants to get the heaviest diamond out of a rough stone. However, this can come at the cost of lowering cut grade. If a diamond is too deep, the carat weight increases with a loss of brilliance due to light leakage. Diamond cutters have to contend with working a stone to its best finished form with the least amount of waste. This strategy depends on the quality of the stone and its final proportions. If two diamonds of equal weight are inspected there can be a noticeable difference in size when viewed from above; arguably the most important view. A well cut 0.90ct diamond for example could have the same width as a poorly cut 1.00ct diamond. This phenomenon is known as spread.

Cut also affects the color of a diamond. This is especially important when considering fancy colored diamonds, where the slightest shift in color could vastly affect the price of the diamond. Most fancy colored diamonds are not cut in to round brilliants, because whereas the round brilliant is prized for its ability to reflect white light, the most important characteristic in a fancy colored diamond is its color, not its ability to reflect white light.

References

- ^ "Expedition Magazine - Penn Museum". www.penn.museum. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ "A History Of Diamond Cutting | Antique Jewelry University". Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ Manutchehr-Danai, Mohsen, ed. (2009), "Agastimata book", Dictionary of Gems and Gemology, Springer, p. 10, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72816-0_262, ISBN 978-3-540-72816-0

- ^ "Bonhams : Two highly important Sultanate gem-set gold Rings made for Mu'izz al-Din Muhammad bin Sam (AH 569-602/ AD 1173-1206), the first Muslim conqueror of Delhi (2)". www.bonhams.com. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ "Mughal Cut Diamonds – The Search Continues". Retrieved 2024-01-02.

- ^ "Book Review: American Cut, The First 100 Years by Al Gilbertson | GemWise / rwwise.com". Retrieved 2023-12-21.

- ^ "Old European Cut Diamonds". Jewels by Grace. Retrieved 2023-12-21.

- ^ Federman, David (2022-08-10). "Gem Portrait: Old European Cut Diamonds". Worthy. Retrieved 2023-12-21.

- ^ U.S. patent 694215A

- ^ U.S. patent 732118A

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Marcel Tolkowsky (1919). Diamond Design. Spon & Chamberlain.

- ^ "What did Marcel Tolkowsky really say?". Archived from the original on 2006-08-27.

- ^ "Russian gemmological server". Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ "Crown and Pavilion Angles". www.pricescope.com. PriceScope. 2009-04-08. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Cut fuels the diamond’s fire, sparkle, and brilliance. gia.edu

- ^ Diamond shapes. Diamond shapes. Retrieved on 2013-08-20.

- ^ Peter Yantzer, American Gem Society Laboratories (2005-03-18). "The Effects of Indexed Upper Half Facets".

- ^ Marcel Tolkowsky (1919) Diamond Design, Figure 37. Spon & Chamberlain. Folds.net.

- ^ W. Eulitz (1968). "The Optics of Brilliant-Cut Diamonds". Gems and Gemology. 12 (9): 263–271.

- ^ Yariv Har (June 2, 2009). "Gemstone with 81 facets". United States Patent D593,440.

- ^ Paulsen, Jasper. Graph of "How pavilion angle and girdle thickness affect the best crown angle and table size".

- ^ Harding, Bruce. "Faceting Limits".

- ^ Thomas M. Moses. "Diamond cut and grading system". GIA Laboratory and Research.

- ^ Diamond grading. gemappraisers.com

- ^ Jump up to:a b Naturski, Sebastian. "The Diamond Cut – How to Maximize your Diamond's Sparkle". Your Diamond Teacher. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "New GIA Diamond Grading Report and GIA Diamond Dossier". diamondcut.gia.edu. Gemological Institute of America Inc. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

Further reading

- Antique Jewelry University – A History of Diamond Cutting

- Bruton, Eric. (1979). Diamonds, 2nd ed. Chilton Book Co. ISBN 0-8019-6789-9

- Cipriani, Curzio, Borelli, Alessandro, and Lyman, Kennie (US ed.) (1986). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Gems and Precious Stones, pp. 58–68. Simon & Schuster, Inc.; New York, New York. ISBN 0-671-60430-9

- Malecka, Anna (2017). Naming of the Koh-i-Noor and the Origin of Mughal-Cut Diamonds, The Journal of Gemmology, no. 4. 38(8).

- Pagel-Theisen, Verena. (2001). Diamond grading ABC: The manual (9th ed.), pp. 176–268. Rubin & Son n.v.; Antwerp, Belgium. ISBN 3-9800434-6-0 [1]

- OctoNus Software has posted several diamond cut studies, by various authors. OctoNus, Moscow State University, Bruce Harding, and others have posted work there.

- Holloway, Garry (2000-2004). HCA: defining ideal cut diamonds is a detailed explanation of the "Holloway Cut Adviser". A web service that uses this software is available.

- Blodgett, Troy; et al. (GIA) (2006) "Painting and Digging Out", GIA article 2006.

- Ware, J. W. (1936). New Diamond Cuts Break More Easily, pp. 4. Gemological Institute of America, USA, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Winter 1936)